Why does arts and culture need to think about climate justice?

At Creative Carbon Scotland we are currently working on a project around climate justice and the ways in which it is relevant to the Scottish arts and culture sector. In this blog post I’ll introduce why we think this is important, discuss the context in Scotland, and share some of the results of a discussion event we held on 17 May 2022.

Read about our Climate Justice project here

International Climate Justice

The basic idea behind climate justice is quite simple:

-

Those who are worst affected by climate change are the poorer and more disadvantaged and are generally those who have contributed least to the greenhouse gas emissions that cause it. Climate change is thus fundamentally an injustice.

-

Climate change results from, interacts with and exacerbates inequalities and injustices that already exist in the world. We thus need to address climate change in a way that understands and connects with these.

The logical consequences of the basic ideas are wide ranging and present major challenges as well as opportunities for more effective action on climate change.

Climate justice is not a new concept. The term has been in use for decades, stemming primarily from grassroots movements and organisations based in areas most affected by climate change. A foundational document, the Bali Principles of Climate Justice, was signed in 2002. These principles in turn pay tribute to the now 30-year-old 1991 Principles of Environmental Justice, a statement released to highlight connections between pollution and racism in the USA.

The concept has gradually been pushed from the fringes to centres of power. As of 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which advises the United Nations on climate change science, now recognises many of the core ideas behind climate justice. In their most recent ‘assessment report’ they stated:

‘Vulnerability... differs substantially among and within regions, driven by patterns of intersecting socioeconomic development, unsustainable ocean and land use, inequity, marginalisation, historical and ongoing patterns of inequity such as colonialism, and governance.’

International negotiations on climate change are now frequently framed in terms of justice, with poorer countries pointing to the responsibility of wealthy nations that have historically contributed the most to climate change to now contribute more to the cost of addressing it. The interaction between climate change and inequalities is also increasingly highlighted, with UN Climate Conference held in Glasgow in 2021 including a day officially devoted to ‘gender’ as part of its programme.

Climate justice in Scotland

The Scottish government made history in March 2012 by passing a motion ‘strongly endors[ing] the opportunity for Scotland to champion climate justice’ and establishing a £3million ‘Climate Justice Fund’ aimed at minimising the effects of climate change in the world’s poorest countries. Climate Justice remains an official part of Scottish Government policy and led to the establishment of a ‘Just Transition Commission’ in 2018. As a result, while the situation is not perfect, the Scottish context is in some ways more amenable to work on climate justice from the arts and culture sector than in the rest of the UK.

Although, the gravest injustices resulting from climate change occur on an international level that can feel hard to access from the perspective of Scottish arts and culture. There are a few key issues at play here in Scotland that are both local and connected with international issues. These include:

-

The North Sea oil and gas industry, which is a major employer in Aberdeenshire but has frequently been critiqued for threats to workers’ rights and the use of ‘hire and fire’ practices. To address climate change, the North Seas oil and gas industry must end and there is a pressing need to provide workers with routes into alternative jobs.

-

Mossmorran and Grangemouth, Scotland’s two largest oil and gas processing sites, which have significant health impacts for local communities who have complained of air, noise and light pollution, and have repeatedly been fined by the Scottish Environmental Protection Agency.

-

‘The Green Lairds’, a term coined to describe those buying up land in the Highlands for the purposes of tree planting. This is an important activity, but approaches have been criticised by for misrepresenting the area as a wilderness rather than people’s home and failing to consult with residents, leading to comparisons to the Highland clearances. Community ownership has been suggested as an alternative model for tree planting with an example being Tarras Valley, the largest community buyout in Scttish history.

-

Fuel poverty, which affects a quarter of Scotland’s population due to combination of cold winter temperatures and poorly insulated housing stock. Improving home insulation addresses this while also reducing greenhouse emissions from home heating.

-

Scotland’s island communities, who are facing the impacts of climate change first with increased flooding, erosion and extreme weather already affecting residents to a much greater extent than in Scotland’s mainland cities where decisions about climate policy are most frequently made.

What role the arts can have

‘When I was a little girl I was taught the importance and impact of words. In my culture there is a proverb that goes, 'e pala ma’a ae lē pala upu'. It means that even stones decay, but words remain. A lesson in knowing how words can be wielded. How text can change everything. How each word you use is weighted. How switching one word or number can reframe worlds. How “climate action” can be vastly different from “climate justice”.’

This quote comes from a speech made at the COP26 United Nations climate conference by Brianna Fruean, a Samoan climate activist and member of the Pacific Climate Warriors group. It draws attention to how intangible matters of how we understand and express climate change can matter just as much as material issues of greenhouse gases and finance.

Climate justice recognises this by framing the issue not just as technical and scientific but also as social and cultural, entangled with social issues of inequality and discrimination. As an organisation, we have continually made the case for how arts and culture are needed to work seriously on the social dimensions of climate change, but the framing offered by climate justice makes this case even more strongly. Questions around ethics, social justice, and the influence of our history simply cannot be separated from the need to reduce global carbon emissions.

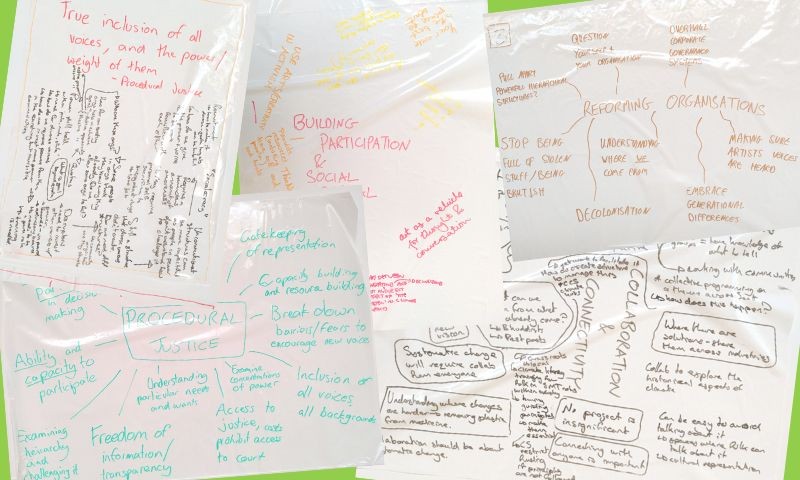

In May 2022 we held a discussion event with people coming from backgrounds in the arts, climate change and social justice to discuss the ways in which climate justice relates to arts and culture. The event featured contributions from speakers Judi Kilgallon of the Improvement Service, Aekus Kamboj of the Council of Ethnic Minority Voluntary Organisations (CEMVO) and theatre-maker and campaigner Ink Asher Hemp. This was followed by group discussions to identify keys issues and areas that we wanted to work on.

Here are some of the key thoughts from the presentations and ensuing discussions:

-

We need to decarbonise the arts and culture sector in a fair and equitable way. This means being aware of how removing plastic straws has a negative impact on people with certain disabilities who depend on them for example.

-

The arts can be a route to ‘procedural justice’. This means that for climate change policy to be fair the procedure used to create it must also be fair. This means giving everyone an opportunity to understand and influence plans. Arts venues can provide ideal spaces to help make this possible.

-

Artistic work can frame how we think about climate change through imagery and storytelling, helping to make the sometimes-hidden connections between climate change and issues like global inequality clear and tangible.

-

If climate change is interconnected with other injustices and inequalities, when working on environmental sustainability we might consider collaborating with organisations who are not primarily focused on climate change but are drawing these connections.

-

When engaging with climate change, it is important for artists and arts organisations to think about what narratives we are highlighting. Artistic work can provide an opportunity for less-heard voices to reach new audiences. This might mean platforming the stories of indigenous communities on the front lines of climate change for example.

-

We should do more to seek out and promote the work of artists of colour, disabled artists, working class artists and others who are not well-represented among mainstream environmental movements. This will help make the ideas and approaches available through the arts more varied and more representative of society.

-

When using the arts to engage communities with climate change, we should listen to their needs and co-design approaches in conversation with them, rather than imposing a top-down approach that might not be appropriate.

These are just a few of the initial ideas, which will form the basis for numerous avenues of enquiry. If you are interested in learning more about this project or contributing your own expertise to the research. Please contact [email protected].

Local Journeys for Change

This project is part of the IETM Local Journeys for Change activity which is supported by the European Union as part of IETM Network Grant 2022-2024 NIPA: the New International in the Performing Arts.

Local Journeys for Change (LJC) is the new IETM programme for IETM members; aimed to empower them to bring positive change to their local professional context, local communities or policy-making field.

For this first edition of the programme, focused on the theme of Inclusivity, Equality and Fairness, the LJC selection committee selected 24 projects led by IETM members from 22 countries worldwide. They will benefit from training, mentorship, peer-review exchange and financial support to implement their projects in their respective local communities.